Periodic charts are a must have in every chemistry classes. A periodic chart (or also called a periodic table) is a table of elements that are ranked according to their atomic numbers, atomic mass, chemical properties, etc. Periodic charts are also arranged by a color coding scheme to help us identify which group of elements they belong to (e.g., some elements belong to the alkaline group so they have a particular color for that, some elements belong to a metal group so they belong to another color group, and same goes for the non-metal elements, etc.). If you bother to ask why and how such a table exists, well, we will help you trace back its history and development.

Precursors to the periodic table

Contrary to the popular notion (and what has been usually taught at schools), it wasn’t the Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev who originally invented the periodic chart, although he was credited for developing the periodic chart just like the one that is in use today.

Mendeleev’s improvement on the periodic chart was based on the ideas brought about by other scientists, particularly Antoine Lavoisier and Stanislao Cannizzaro. But before we would jump into that phase, we must know first that the discovery of the elements is necessary in order to assemble, construct and develop the periodic chart.

There are metals such as gold, silver, tin, copper, mercury, lead and others which we consider “antique” metals because they had been discovered way, way back during the times of Aristotle and Plato.

During the Middle Ages – also called the “age of enlightenment” in the world of science – the first known incidence where an element was scientifically formed, thanks to German merchant and alchemist, Hennig Brand. Brand had made many attempts to turn base metals (metals that are easy to oxidize or rust) into precious metals. It had been attempted by not only by Brandt but also by other amateur chemists at that time, to fabricate a precious metal (supposedly) known as the “philosopher’s stone.”

He was, of course, unsuccessful in his many attempts to create precious metals out of the base metals. In 1669 Brand heated residues from boiled urine (which had been left over from his previous attempts to create precious metals) from his furnace until the glassware containing the urine residue exploded, and led to the liquid dropping out and bursting into flames. It was the first discovery of phosphorus. He kept this discovery as a secret until Robert Boyle rediscovered phosphorus and introduced it to the public.

Brand’s sheer luck-out of the discovery of phosphorus launched the discovery of other elements. By 1809, there were at least 47 elements discovered, and chemists began a method of patterning their characteristics and properties. Boyle set the first definition of an element by 1661 as a substance that cannot be separated through a chemical reaction. This definition has been taught in schools for centuries.

Many years later, we jump to the time where the modern periodic table’s roots lay. French chemist Antoine Lavoisier published the Elementary Treatise of Chemistry, which formed the basis of the periodic chart. It contained the list of metal and non-metal elements, which was understandably incomplete at that time.

In 1817 German chemist Johann Wolfgang Dobreiner discovered the atomic weight of an element was similar to another in that group of elements. For instance, the atomic mass of strontium was similar to the atomic mass of calcium and barium. So since finding the similar chemical properties of certain elements, he proposed to classify the elements according to their properties, and he gave these classifications as triads – just like the triad of calcium, strontium, and barium. Dobreiner categorized other triads: chlorine, bromine and iodine; sulfur, selenium and tellurium; and lithium, sodium, and potassium.

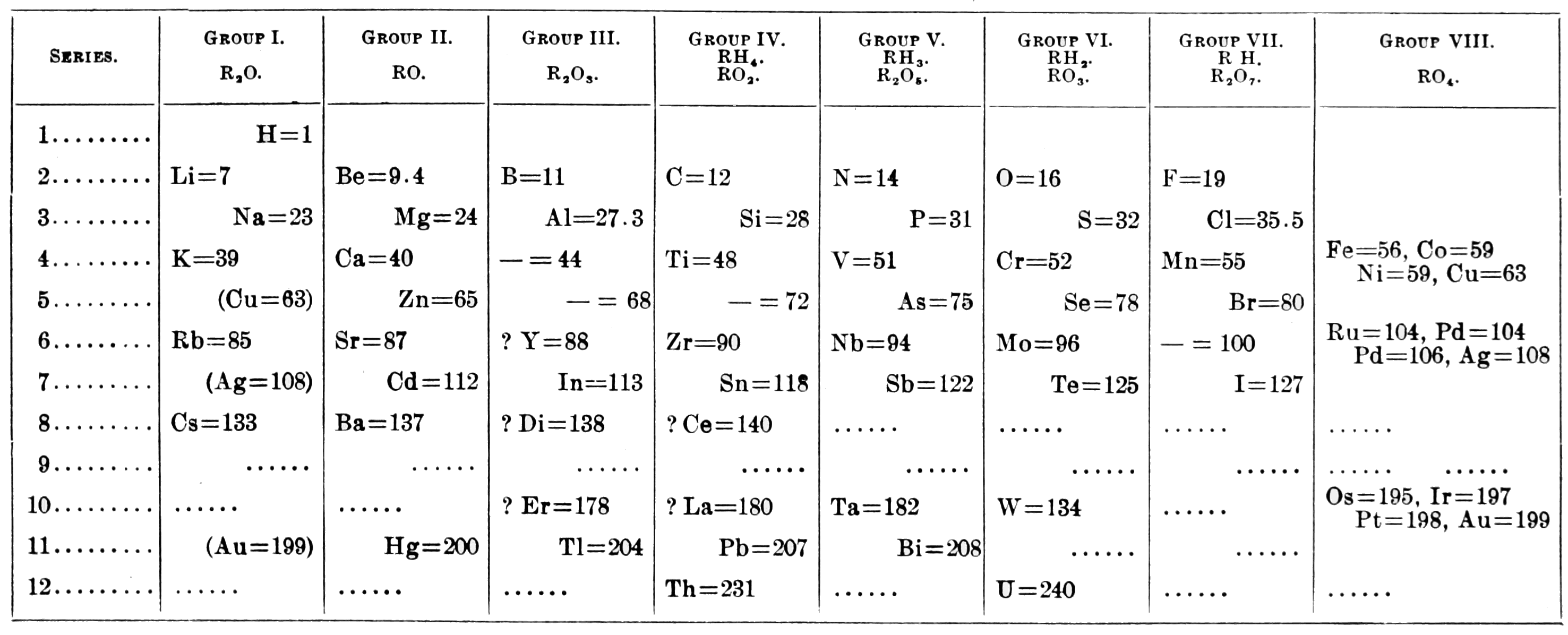

In 1869 Mendeleev began constructing and developing the periodic chart into the modern periodic chart we use today. He arranged the elements by atomic mass, and provided empty spaces in his table, predicting that there would be more elements to be discovered in the future. However, Mendeleev didn’t include the noble gases in his chart, and these would be added by Scottish chemist Sir William Ramsay and Lord Rayleigh in 1894.

As time passed, there were several more improvements on the periodic chart. English chemist William Odling re-arranged the formation of the periodic table and found the right groups for thallium, lead, mercury, and platinum. English physicist Henry Moseley proved that the recurring trends in some elements – called periodicity as opposed to atomic mass – provided the basis for their atomic number. Another English physicist James Chadwick discovered the neutron in 1932, which led to the complete basis for the periodic chart. Nobel Prize-winning American chemist Glenn T. Seaborg discovered actinides and lanthanides, as well as the transuranic elements which occupy the bottom of the periodic table.

Several other proposals and studies have led to the continuous improvement and refinement of the periodic table, which began thanks to Mendeleev. In fact, element no. 101, Mendelevium, was named in his honor.

Helpful links

- The elements of the periodic table sorted by the discovery year

The elements of the periodic table sorted by the discovery year - Periodic table history

History of the periodic table of chemical elements - History of the periodic table – Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia